Luxmeter App versus measuring device: Are smartphones suitable for measuring illuminance?

We are faced with this question ever more frequently because the benefit is obvious. Such apps are completely free or available at a very low price. It would really be smart to replace a luxmeter, which, depending on the manufacturer and the accuracy, costs between 100 and 2,000 Euros, with an app for the smartphone which nearly everyone has anyway.

As an accredited lighting laboratory we can only smile at the idea of anyone trying to determine a photometric parameter with a »telephone«. Yet our curiosity motivated us to get to the bottom of this matter/ to look into this matter. So we started looking for different luxmeter apps for different operating systems so that we could test them. We wanted to find out how well they compare with a calibrated class A luxmeter from our laboratory.

The hardware

For this test we used different series of iphones as well as Sony, Samsung and Nokia devices.

| Manufacturer | Operating system |

| iPhone5 | iOS |

| iPhone 5S | iOS |

| iPhone 6 | iOS |

| Sony Xperia Z1 | Android |

| Sony Xperia Z2 | Android |

| Samsung Galaxy S5 | Android |

| Nokia Lumia 925 | Windows Phone |

The software

We chose the following apps, most of them free, and installed them on each of the systems:

| Name | Manufacturer | Operating system | Calibration option | Price |

| Galactica Luxmeter | Flint Soft Ltd. | iOS | no | free |

| LightMeter by whitegoods | Whitegoods | iOS | yes | free |

| LuxMeterPro Advanced | AM PowerSoftware | iOS | yes | 7,99 € |

| Luxmeter | KHTSXR | Android | yes | free |

| Light Meter Pro | Mannoun.Net | Android | yes | free |

| Lux Light Meter | Geogreenapps | Android | yes | free |

| Sensor List | Ryder Donahue | Windows Phone | yes | free |

Our reference

We conducted the reference measurements with an Illuminance meter from PRC Krochmann (Model 106e, special model, class A). And of course with valid retraceable calibration.

The light sources used

For this test we chose three different light sources:

-> Low voltage halogen lamp

-> Compact fluorescent lamp (correlated colour temperature: 2,700 K)

-> LED (correlated colour temperature: 3,000 K)

In order to keep everything simple and transparent we have restricted ourselves in this article to presenting the results achieved with the LED light source.

Our test setup

The test took place in a room without daylight, unaffected by any artificial light sources. With the indicated light sources we set reference illuminances of 100 lx, 500 lx and 1,000 lx one after the other on a horizontal surface. To do this the head of the photometer of the PRC luxmeter was positioned axially below the luminaire (Gamma 0°). Then, one after the other, the different smartphones, each with their own measuring app, were used to measure the illuminance. For this the front camera, the brightness sensor on the display of the smartphone, was used. The sensor or front camera was positioned exactly at the reference point where the head of the photometer of the luxmeter had previously been positioned. This setup was maintained for all the apps with the exception of the paid app »Luxmeter Pro Advanced« since this requires the reflected light from a surface as input. The numerous settings in this app for the type of light source, the distance from the illuminated surface etc. were also adjusted. With some apps calibration is possible. This calibration was also carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions, each time with a reference calibration of 100lx.

Evaluation

During our test we found out that, although it was possible to calibrate some of the apps to a certain value, it was frequently not possible to set this value accurately enough. So calibration was often in large increments or the reference value 100lx could not be set since the app could only be calibrated to a maximum of 34lx (iPhone 5 in combination with »LightMeter by whitegoods«). The deviations from the reference luminance were in part extremely high (up to 113% in the combination of Samsung Galaxy S 5 with the app »Lux Light Meter« from Geogreenapps). When using a reference value of 500 lx the display of the smartphone showed 1,063 lx. The lowest deviation in percent (3%) occurred with an iPhone 5 in combination with the app »LightMeter by whitegoods«. When a reference value of 500 lx was used, this smartphone displayed 484 lx. We cannot conclude however that precisely this combination will always lead to the lowest possible deviation. When a reference value of 100lx was used this app on the same smartphone was right off the mark by 89% with a displayed value of 11 lx.

The general observation is that the displayed values on the Sony devices and the Samsung and Nokia smartphones were well above the reference values, while as a rule the the iphones displayed values well below the reference values. The median deviation from the reference value measured by all the apps on the Android smartphones and on the Windows phones was on average 60% above the reference value. The median deviation of all values measured with all the different iphones was approx. 60% below the reference value.

We also noticed that the apps installed on the Samsung smartphone and on the Sony devices apparently had no influence on the value displayed. It seems that with these devices the »brightness sensor« and not the camera is used to measure illuminance. With some Samsung models it is possible to switch to the LCD test mode via the key combination *#0*#. Here, using the function »Light sensor«, you can read the alleged illuminance without installing an app. The installation of an app seems superfluous here since it apparently only serves to display a value. Nevertheless, all the values displayed by these devices also deviated by 37% to 113% from the reference value.

Does the same hardware in combination with the same app also lead to the same results?

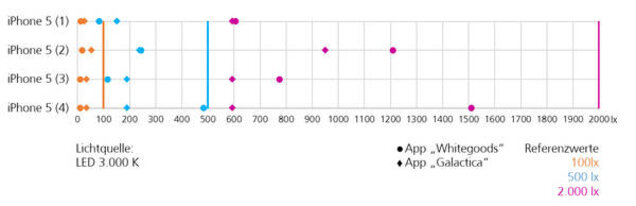

Independent of the large fluctuations in the measured values we asked ourselves whether structurally identical smartphones with the same app also display the same illuminance values. To test this we used 4 structurally identical phones of the type »iPhone 5« each with the apps »Galactica« and »LightMeter by whitegoods«. Unfortunately we suffered disappointment here, too. The diagram shows that in some cases, with the four smartphones we tested, completely different measuring results were achieved.

We suspect that the reason for these fluctuations lies in the tolerances of the components built into the phones. These are tolerances which the user does not notice in everyday use but which in direct comparisons have a great effect on the displayed illuminance values.

Is the percentage deviation from the reference value always the same?

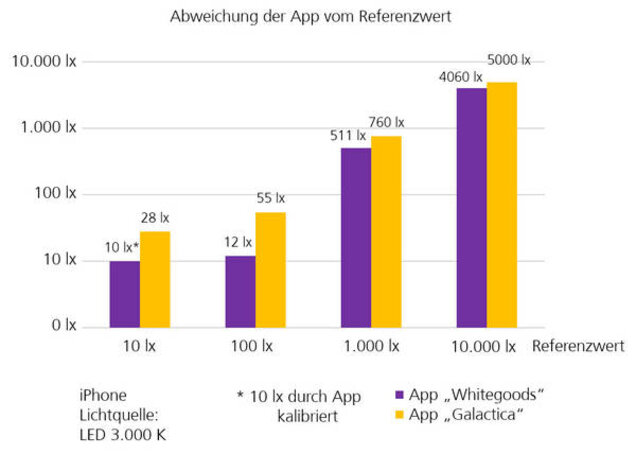

If you always use a smartphone with the same app, you might assume that you could still use it quite well for measuring illuminance if you already know the percentage deviation from the reference value. But is the percentage by which the value displayed by the app deviates from the reference value the same for different illuminances? To pursue this question we carried out measurements of illuminance at 10 lx, 100 lx, 1,000 lx and 10,000 lx with an iPhone 5 on the optical bench of our black laboratory. The increments can be set very accurately by adjusting the distance between the light source and the receiver. The LED luminaire with 3,000 K was used here again as a light source. In this test we looked at the values of two different apps.

As experience has shown, the values of the apps deviate from each other – in certain cases by up to 358% (12 lx to 55 lx at a reference value of 100 lx). If we look at the percentage deviations from the reference values, then no regularity of any kind is apparent.

The »Galactica« app was 180% above the reference value at 10 lx and 50% below the reference value at 10 000 lx. The »LightMeter by whitegoods« app was calibrated at 10 lx. At a reference value of 100 lx it was 88% off the mark and at a reference value of 10 000 lx 59%. All other values of the luxmeter apps were well below the reference values. There was no constant percentage deviation from the reference values. And quite incidentally we discovered that using the back camera rather than the front camera of the smartphone often produced completely different values. In addition to this, some apps never display 0 lx, not even when the camera is fitted with a lightproof cover.

Conclusion

The results prove that serious measurement of illuminance is only possible with professional hardware. This has a V(λ)-adjusted sensor which ensures that evaluation of the incident radiation is performed according to the brightness sensitivity curve of the human eye in daylight. In addition, a cos-true evaluation is important, that means that a weighting of the incident radiation is performed according to the angle of incidence on the sensor. Smartphones can do neither the one nor the other, since otherwise their original function would not be guaranteed.

It is not the app manufacturers' intention that a smartphone should replace a professional luxmeter. The fact that some apps work with so-called calibration functions sounds professional and smart but unfortunately it is often not possible to set the value accurately. Even if it is possible, the benefit is very small since the values outside the calibrated value are subject to extreme fluctuations. Even when using the same app in structurally identical smartphones different measuring results are achieved.

Therefore apps are unfortunately not really of any great assistance for measuring illuminance and not even any use to obtain a general idea of the illuminance value. On the contrary: They lead the user in the completely wrong direction.